Today, we’re joined by Faisal Zain, a healthcare expert specializing in medical technology and innovation in surgical devices. With years of experience observing the intersection of technology and patient care, he offers a unique perspective on the evolving field of spinal medicine. We’ll explore the critical shift toward less invasive, motion-preserving techniques, the growing importance of a surgeon’s holistic and communicative approach, and how advanced tools like robotics are reshaping outcomes for patients facing complex spine surgery.

The article highlights Dr. Melikian’s expertise in motion-preserving techniques like artificial disk replacement. Could you elaborate on how these techniques differ from traditional fusion surgery and share an example of how this approach has significantly improved a patient’s long-term mobility and quality of life?

Of course. The difference is truly night and day for the right patient. Traditional fusion surgery is essentially a welding process for the spine; the goal is to stop motion at a painful vertebral segment by fusing the bones together into one solid piece. While it can be very effective for pain, it inherently limits flexibility. Imagine trying to bend a rod that used to be a chain. In contrast, motion-preserving techniques, like the artificial disk replacements Dr. Melikian is known for, aim to restore the natural biomechanics of the spine. We replace the damaged disk with a sophisticated implant that mimics the original’s ability to bend, flex, and twist. I think of a patient who was an avid golfer, told that fusion was his only option. He was devastated, feeling that his passion, his main way of de-stressing, was being taken away. By opting for a disk replacement, he was back on the course within months, not with a stiff, guarded swing, but with the fluid, powerful motion he had before his back pain started. It didn’t just fix his pain; it gave him his life back.

Dr. Lanman is noted for his comprehensive, holistic approach. Can you walk us through the step-by-step process you use to evaluate a patient’s lifestyle before resorting to surgery, and what are some of the most effective non-surgical interventions you typically recommend first?

A truly holistic evaluation, like the kind Dr. Lanman champions, treats the patient as a whole person, not just a spine on an MRI scan. The first step is always a deep, conversational dive into their daily life. I want to know everything: what do you do for work? Are you sitting at a desk for eight hours or are you a contractor lifting heavy materials? What do you love to do for fun? How is your pain affecting your family, your mood, your sleep? This builds a complete picture. From there, the second step is a physical assessment that connects their story to their body, looking at posture, muscle imbalances, and movement patterns. Only after understanding this full context do we move to the third step: recommending interventions. Before ever discussing a scalpel, we exhaust options like targeted physical therapy to strengthen supporting muscles, anti-inflammatory nutrition plans, ergonomic adjustments to their workspace, or even mindfulness practices to manage the perception of chronic pain. The goal is always to find the least invasive path to a healthy, active life.

Dr. Siddique uses advanced technologies like robotic and image-guided surgery. How have these tools specifically changed outcomes for complex outpatient procedures, and what metrics do you use to measure their impact on patient recovery times and surgical precision?

These technologies have been revolutionary, particularly in the outpatient setting. Think of robotic and image-guided systems as a hyper-accurate GPS for the surgeon. They create a real-time, 3D map of the patient’s unique anatomy, allowing the surgeon to plan and execute every step with sub-millimeter precision. This has dramatically changed outcomes by enabling smaller incisions. Instead of a large opening with significant muscle disruption, we can use a keyhole approach. This means less blood loss, a substantial reduction in postoperative pain, and a lower risk of infection. The metrics we use to measure this impact are very clear. We track recovery time in hours, not days; patients are often walking within a few hours of surgery. We also see a significant drop in revision surgery rates because the initial placement of hardware is so accurate. We measure precision by comparing preoperative plans to postoperative scans, confirming that implants are placed exactly where intended, which is fundamental to long-term success.

Several surgeons, including Dr. Nagasawa, are praised for a “communication-first” strategy. Beyond just explaining a procedure, what specific steps can a surgeon take to build trust with a patient who is fearful, ensuring they feel respected and fully educated about their options?

Building trust goes far beyond reciting risks and benefits. A communication-first strategy, like the one practiced by Dr. Nagasawa, is about creating a genuine partnership. The first step is to actively listen and validate the patient’s fear. A surgeon should start by saying, “I know this is scary. Let’s talk about what worries you most.” This immediately changes the dynamic from a lecture to a conversation. The next step is to demystify the process. I encourage surgeons to use anatomical models, draw simple diagrams, and walk through imaging with the patient, explaining what they see in plain language. Most importantly, a surgeon builds trust by presenting all viable options—including non-surgical ones—with equal weight and enthusiasm. When a patient feels the surgeon is an advisor helping them choose the best path for their life, rather than a salesman for a specific procedure, it fosters a profound sense of respect and security. It’s about empowering the patient to be the final decision-maker for their own body.

The text mentions that in 2023, there were over 30,000 spine surgeries. When a patient comes to you for a second opinion, what key diagnostic details or red flags most often lead you to recommend a different, less invasive path than what was originally proposed?

That statistic of over 30,000 surgeries is exactly why second opinions are so vital. The most common red flag I see is a disconnect between the patient’s story and their imaging. A surgeon might see a bulging disk on an MRI and immediately recommend a major surgery, but the patient’s symptoms—the location and type of pain—don’t perfectly align with that finding. That’s a huge signal to pause and investigate further. Another key detail is the absence of a thorough trial of conservative care. If a patient is told they need a spinal fusion but they haven’t engaged in a dedicated, high-quality physical therapy program for at least six to twelve weeks, that’s a major red flag. Often, a less invasive path emerges not from a new scan, but from truly listening to the patient’s goals and history and realizing that the initial, more aggressive plan may not have been tailored to them as an individual.

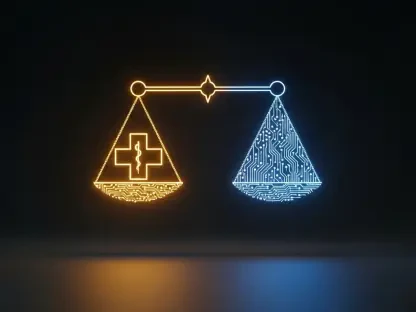

What is your forecast for the future of spine surgery, particularly regarding the balance between high-tech advancements like robotics and the increasing focus on holistic, motion-preserving treatments?

My forecast is that these two trends will not compete but will actually merge into a single, powerful approach: personalized, functional restoration. The future isn’t about choosing between a robot and a holistic philosophy; it’s about using high-tech tools to better achieve holistic goals. We will use artificial intelligence to analyze patient data and predict which specific motion-preserving technique will yield the best long-term outcome for an individual’s lifestyle. Robotic assistance will make these delicate, technically demanding surgeries even safer, more precise, and more widely available. The ultimate goal is shifting away from simply “fixing a problem” on a scan and toward restoring a person’s full, dynamic life. Technology will become the essential tool that enables us to deliver on the promise of holistic, motion-focused care with a level of precision we’ve never seen before.